As a (historical) cryptology expert, a few years ago during my work for the DECRYPT project [4], I delved into a fascinating historical mystery that took me back to the year 1575. It was a pivotal year for the Habsburg Emperor, Maximilian II, who was vying for the crown, which was vacant at that time, of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a vast parliamentary monarchy.

While today’s election campaigns are awash with digital media strategies and online propaganda, back in the day, things were a tad different. Maximilian, being a foreign candidate, relied heavily on written correspondence to communicate his political promises and strategies to allies in Poland-Lithuania campaigning for his election. But there was a catch – these letters contained sensitive political information, and there was always a risk of them being intercepted by “the enemies”.

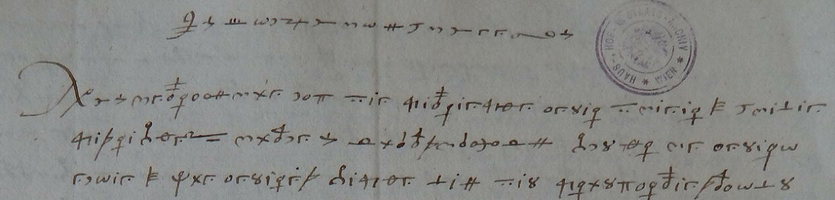

To my surprise, Emperor Maximilian II and his secretaries didn’t rely on the digit ciphers that were already popular at the time, e.g., in the Vatican. Instead, they encrypted their messages using a mix of alchemical symbols, astrological signs, Latin and Greek letters, numbers, and even some characters of their own invention.

What caught my attention was a discovery in Vienna’s state archives by two of my DECRYPT project colleagues (historian Prof. Benedek Láng and his PhD student of that time Anna Lehofer) – five encrypted letters related to Maximilian’s candidacy for the Polish-Lithuanian throne.

Using CrypTool 2, I was able to decipher the ciphertexts partially. Then, with the help of my good colleague and later co-author of two research articles [1,2] and an article for the German magazine c’t [2] about the topic, we we finally were able to decipher like 95% of the letters.

Deciphering Maximilian’s Letters – A Closer Look

Deciphering historical encrypted manuscripts is always a blend of art and science. When I first set my eyes on Maximilian’s letters, I realized that the challenge was not just in the encryption but also in the transcription. Also, I did not even know that the emperor Maximilian II was the author since there were no visible signs of sender and receiver marks on the letters. Only after Michelle suggested that Maximilian II may have been the author (she has a really good intution!) and we finally deciphered his name in one of the letters, we were sure about his authorship. The handwritten letters are filled with symbols that were not easily recognizable. There were alchemical and astrological symbols, Latin and Greek letters, and some characters that seemed entirely unique:

The initial step was to transcribe the symbols of the letters into a machine-readable format. To do this, we translated each symbol into a designated UTF-8 character. It sounds straightforward, but the challenge for us was in identifying and distinguishing between similar symbols.

A peculiar aspect of Maximilian’s ciphers was the use of spaces between words. This provided a significant clue. In most advanced ciphers, spaces (or the lack thereof) can serve as a method of obfuscation. But here, the spaces helped in identifying potential word structures, especially for shorter words.

Using my “Homophonic Substitution Analyzer” component of CrypTool 2, we began the decipherment process. The component uses a hill-climbing algorithm, which starts with a random assignment of ciphertext symbols to plaintext letters (a start key). It then continually refines this key by making small changes, improving the quality of the decipherment using a language model.

However, the tool isn’t just a “set-it-and-forget-it” solution. It requires active involvement. As we interacted with the software, we could manually adjust assignments, fixing correct letter identifications and choosing an appropriate language model based on the text’s suspected language. After several trials, it became evident to us that the letters were written in a German dialect of that era. Michelle, my colleague in this project, came to the conclusion that the letters were written by the sender(s) in a so-called “neutral” Austrian-Bavarian written dialect and in an office style typical of the Early New High German period. She also improved the decipherment significantly by correcting my initial work.

One particularly intriguing discovery in the letters was the use of “nulls” (which are usually meaningless filler characters; here denotated as hash symbols #) in the ciphers. These characters were likely used to confound potential eavesdroppers. But, upon close cryptanalysis and some educated guessing, phrases like “###MAX#IMILI#AN##” and “####DAT#PRAG DEN 5## IULII####1#5#7#5####” (Prague the 5th July 1575) were revealed, indicating the sender’s name, date, and location of dispatch.

The successful decipherment of the first letter paved us the way for the four others. In total Maximilian (or, more probably, one or even multiple of his secretaries) wrote three letters and two letters were written by Jan Chodkiewicz, a nobleman of that time. Some of the letters are encrypted using the same key, while others, though they were encrypted using a different key, were made easier for us to cryptanalyze due to the foundational understanding from the initial deciphering. Thus, this deciphering journey was a dance between manual analysis and algorithmic prowess.

Our Conclusion

In conclusion, our journey into the past showcased the encryption methods of the 16th century Holy Roman Empire. While Maximilian’s ciphers might have been challenging for contemporaries, they are no match for our modern computational power and algorithms. Nevertheless, compared to Vatican ciphers Maximilians ciphers are quite poorly designed and cryptanalysts of the time would have probably been able to also solve the ciphers. All in all it was a very interesting project to read letters that probably no one else was able to read for the last nearly 500 years.

References

If you want to read more details about the decipherment and the historical background, you may have a look at our two research papers [1] and [2]. If you are able to read and understand German, you may have a look at our c’t article [3].

[1] Kopal, Nils, and Michelle Waldispühl. “Deciphering three diplomatic letters sent by Maximilian II in 1575.” Cryptologia 46.2 (2022): 103-127. See https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01611194.2020.1858370

[2] Kopal, Nils, and Michelle Waldispühl. “Two Encrypted Diplomatic Letters Sent by Jan Chodkiewicz to Emperor Maximilian II in 1574-1575.” International Conference on Historical Cryptology. 2021. See https://ecp.ep.liu.se/index.php/histocrypt/article/view/160

[3] Kopal, Nils, und Michelle Waldispühl. Kryptische Propaganda – Entschlüsselt: Briefe von Kaiser Maximilian II. c’t 4/2022.

https://www.heise.de/select/ct/2022/4/2134408482322873782

[4] The DECRYPT project. https://www.de-crypt.org/