Within the collections of the Riksarkivet (the Swedish National Archives) lies a four pages long letter that probably had remained undeciphered for centuries. It was written in 1637 by nobleman Sigismund Heusner von Wandersleben to the Swedish High Lord Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna. Heusner encrypted parts of the letter with a complex cipher and it presented a challenge, which my colleague Michelle Waldispühl and I tackled. The letter was first brought to our attention by our DECRYPT project leader, Beáta Megyesi, who discovered it during her research in the archives and shared it with us. This blog post discusses our systematic approach to cryptanalyze this historical document and the insights we gained from it.

The Discovery of the Letter

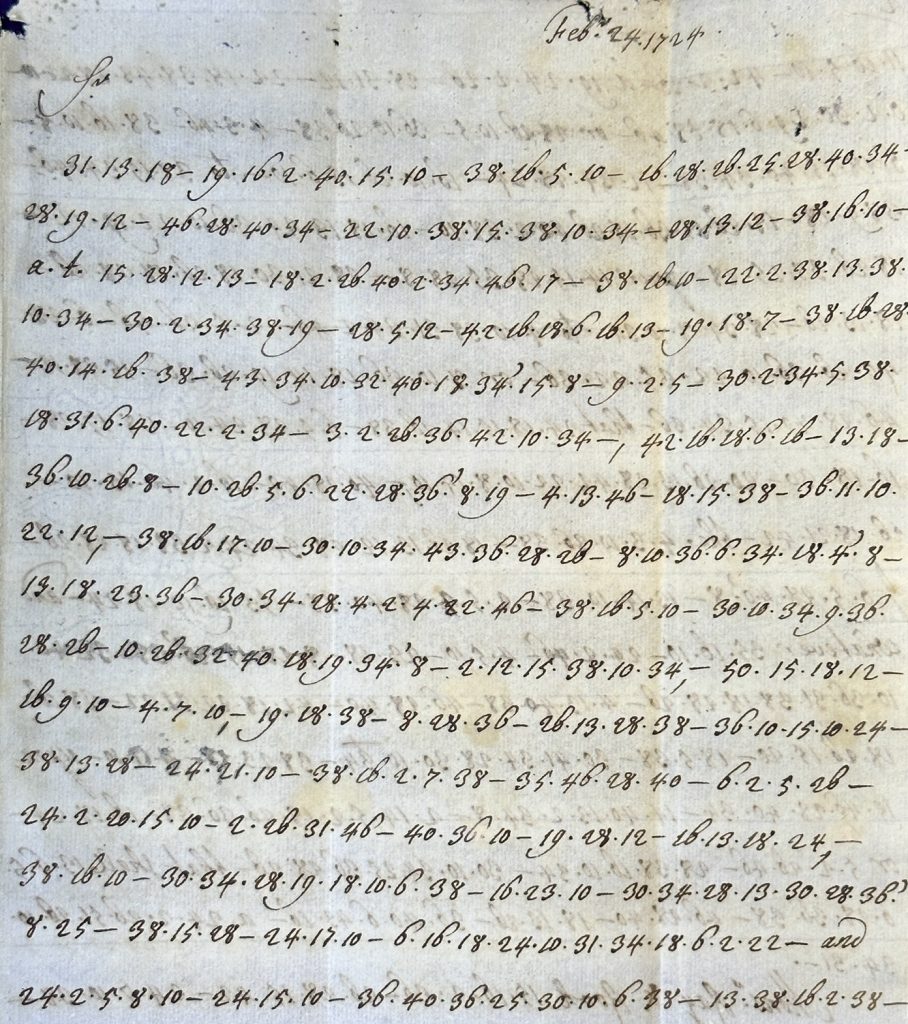

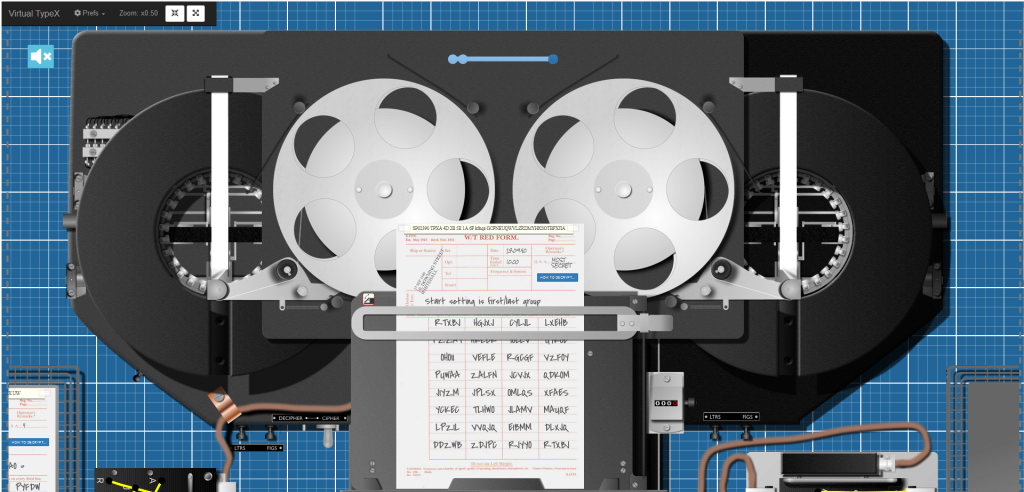

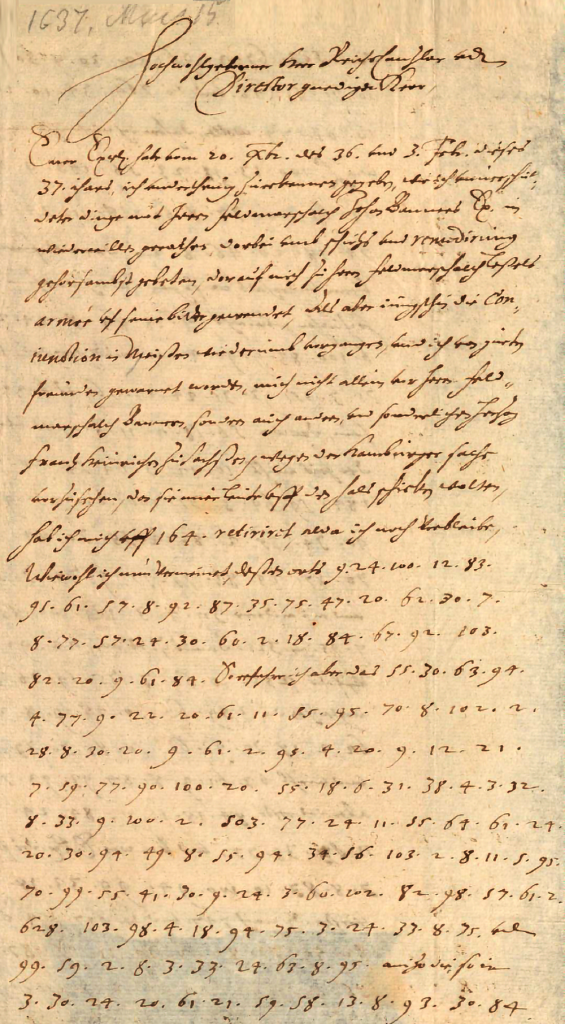

The letter was part of the “Oxenstierna samlingen”, a collection of correspondence preserved in the Riksarkivet (the Swedish National Archives). This particular letter, part of a series written by Heusner von Wandersleben between 1632 and 1638, was the only one encrypted, maybe hinting at the importance of its contents. The DECRYPT project leader Beáta Megyesi found the letter and knew that Michelle and me already successfully worked on German historical encrypted letters. Thus, she brought it to our attention, and we began our collaborative effort to decipher it, which resulted in a mutual research paper (see [1]) as well as a poster, which we, Michelle and me, presented together on the HistoCrypt 2024 in Oxford. The letter, of course, has its own entry in the DECODE database, which you can find here [2]. In the following image, you can see the first page of the partially encrypted letter from 1637.

The Cryptanalysis Process

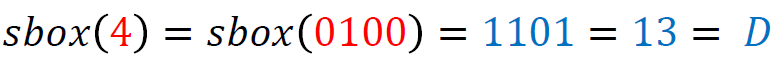

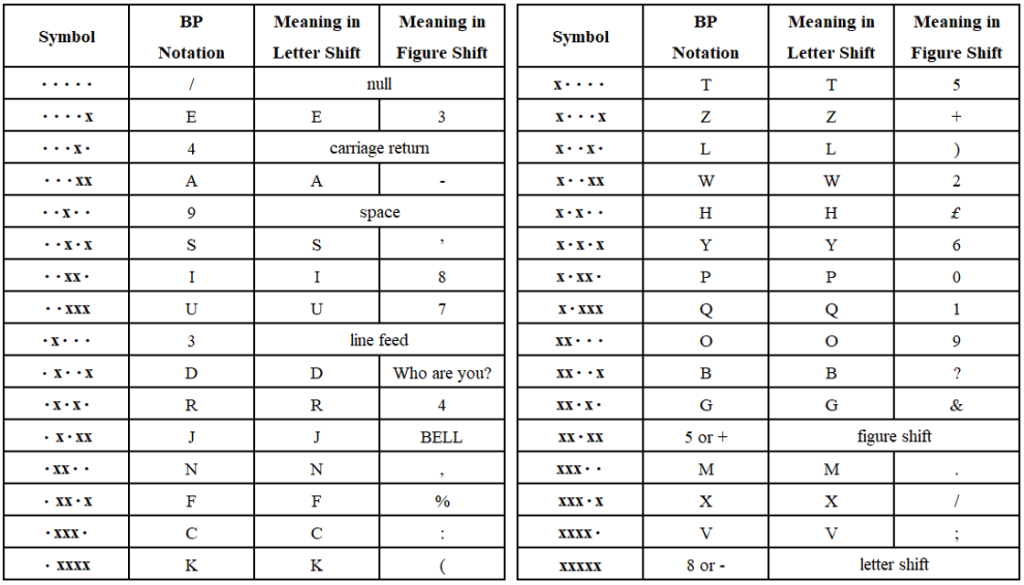

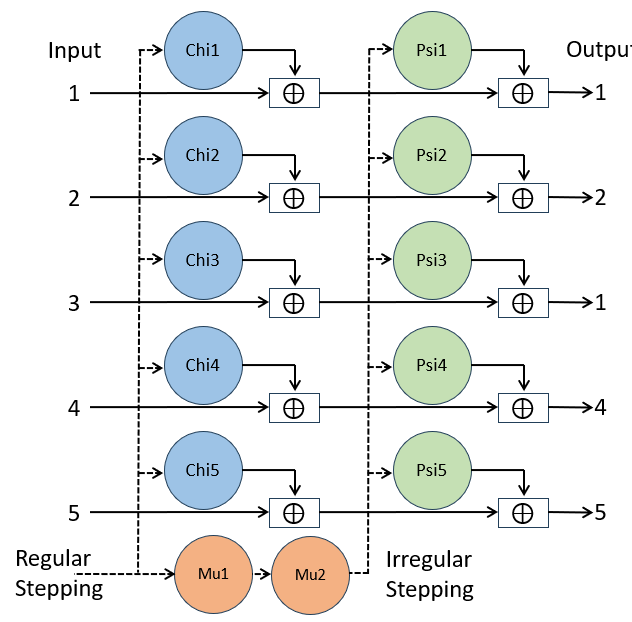

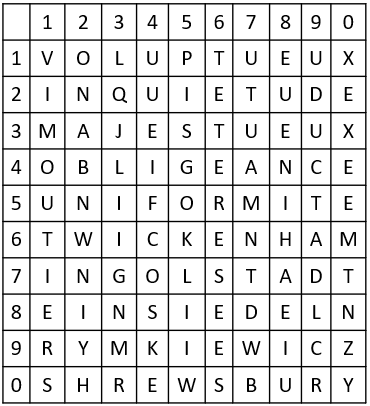

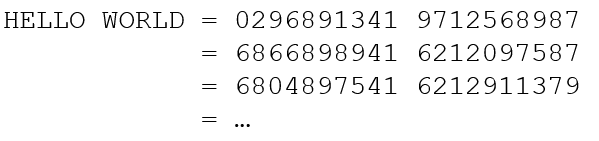

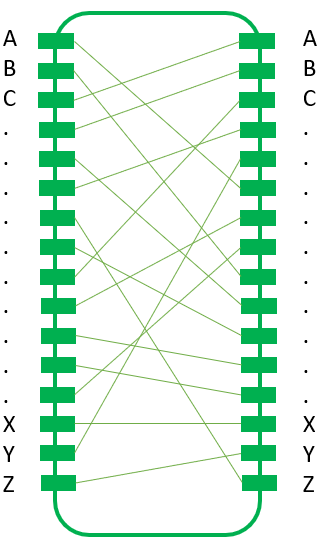

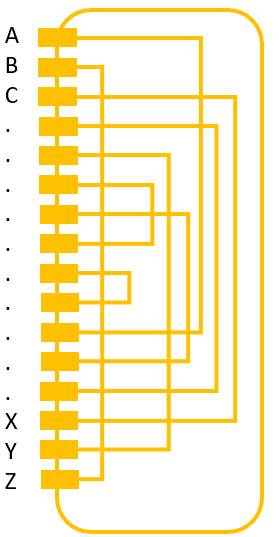

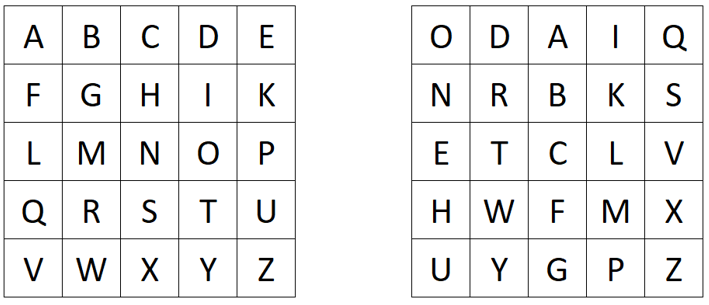

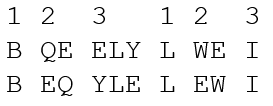

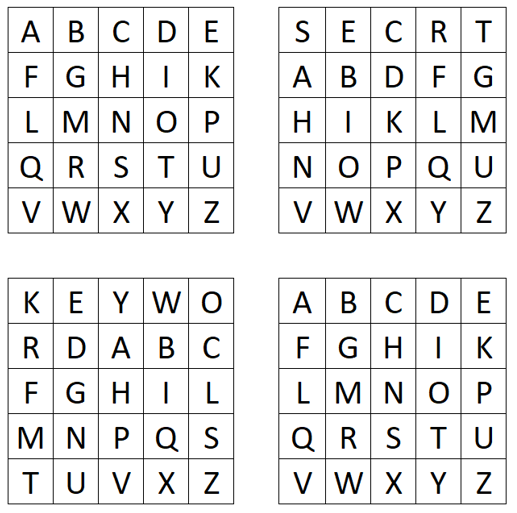

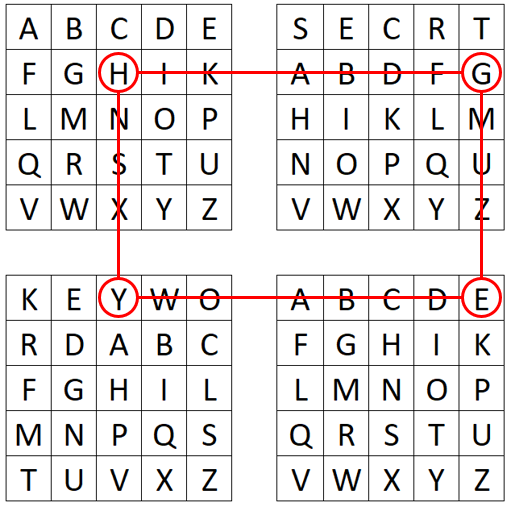

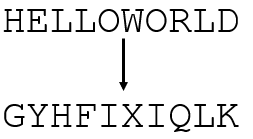

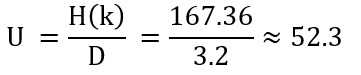

Our first task was to understand the nature of the encryption. The letter’s ciphertext consisted of numbers separated by dots, indicating the use of a homophonic substitution cipher. This cipher type is particularly challenging because it employs multiple so-called homophones to represent single letters, thereby obscuring the original letter frequency as well as patterns that are typically exploited in cryptanalysis of hand ciphers.

To begin the actual cryptanalysis, we transcribed the entire letter with the help of Transkribus.ai, a tool designed for the recognition of historical handwriting. Given the challenges posed by the 17th-century German script, which was written in “Deutsche Kurrent Schrift” (German Kurrent writing), this step required meticulous attention to detail, since the results of the machine-based transcription were good but far from perfect. Every digit and symbol was carefully validated to ensure accuracy in the transcription. We checked of the ciphertext symbols (the numbers) manually and had to correct many of them.

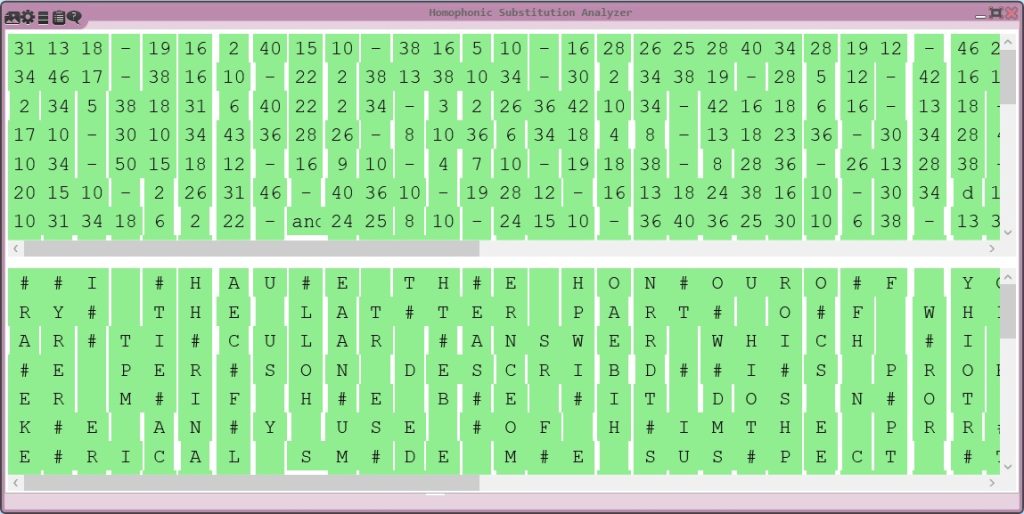

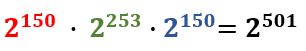

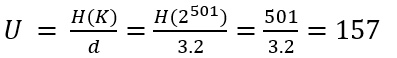

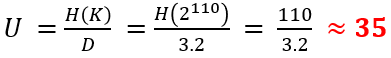

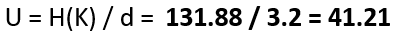

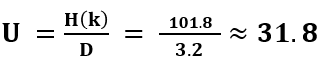

With a complete and accurate transcription in hand, we used to CrypTool 2 (CT2), our open-source cryptanalysis software, that we have frequently employed in our prior work. The Homophonic Substitution Analyzer of CT2 was our primary tool, allowing us to perform semi-automated cryptanalysis of the letter. Through multiple iterations of cryptanalysis and refinement of the assignments of plaintext to ciphertext symbols, we gradually began to uncover portions of the plaintext. During the cryptanalysis, we identified 85 distinct homophones used in the ciphertext. These homophones were not evenly distributed—some letters, such as ‘e’, were represented by as many as eight different numbers, while others had only one. This uneven distribution suggested a deliberate attempt by the cipher creator to complicate decryption efforts. Additionally, the absence of word separators and punctuation in the ciphertext parts added to the complexity, making it difficult to determine sentence boundaries and syntactic structures.

Nomenclatures and the Limits of Decipherment

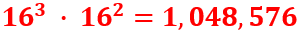

A particularly aspect of the letter was the presence of nomenclature elements—three-digit codes embedded within the ciphertext. These elements likely represented names of individuals or places, critical pieces of information that the sender wanted to protect with additional security. Despite our best efforts, these nomenclature elements remained undeciphered. The only possibility to decipher these is either to find the original key or guess their meaning with the help context. We searched in the DECODE database as well as in the “Hessisches Staatsarchiv” (Hesse State Archive), which holds many original German keys from the Thirty Years’ War, but we were not able to find the original key.

The use of nomenclature elements is consistent with the regular practices of the time, particularly in diplomatic and military communications. Nomenclature elements and their corresponding tables ultimately lead to the invention of code books, which were mainly in use in the 19th and early 20th century.

The Deciphered Letter and a ChatGPT Translation

Here is the unedited transcribed and deciphered German version of the original letter. An English translation generated with ChatGPT is below. The German text still contains errors as well as the undeciphered nomenclature elements (numbers). Also, the originally encrypted parts are all written uppercase:

1637, Mai 15

Hochwohlgeborner Herr Reichchanzlar undt Director gnediger Herr,

Eurer Excell. habe vom 20. Xmbr. des 36. und 3. Febr. dieses 37. ihars ich vnderthenig zuerkennen gegeben, wie ich vnuerrichtetdeter dinge mit Herrn Feldmarschalch Johan Banners Ex. in wiederwillen gerathen, darbei vmb schutzs und remedirung gehorsambst gebeten, darauf mich zu Herrn Feldmarschalch Leßels arm´ee vf seine bitte gewendet. Als aber jüngsthin die Coniunction in Meißen wiederumb vorgangen, sond ich von gueten freunden gewarnet worden, mich nicht allein vor Herrn Feldmarschalch Bännnern, sondern auch anderen, und sonderlichen Hern Frantz Heinrichen zu Sachsßen, wegen der Hamburger Sache vorzusehen, da sie mier leute vff den hals schicken wolten, hab ich mich vff 164. retiriret, alda ich noch verbleibe. Wiewohl ich nun vermeinet, dessen orts DIE ALTE DEUOTION GEGEN DIE CRON ZU FINDEN. So erfahre ich aber das HERR UND KNECHT SEHR GEENDERT UND AM GANZEN HOFE AUSSER DER 503. NICHTT EINER MEHR UFFRECHT SCHWEDISCH, IA DER 628. FAUORISIREI und CARESRIRET aizo die so in SEINEM ABWESEN

dem 503. ZUWIEDER GEWESEN und die 764. UBERGEBEN wollen, daher ich mich nicht wenig Verwundert wie L.EWOLFF DERORTEN NEGOCIIREN SONNEN, deme es furwahr an nottieftigen vnderhalt, in? sogar das ich darfur erschrocken, h¨ochlichen gebracht?, UON EINEM FELDZUG wirdt geredet, WOHIN IST STILL. Es kan aber nichts großes sein, dan die FORCE nicht alda, und man der Zeit nicht BASTANT 808. 385. 184. AUS DEM LANDT ZU TREIBEN da 503. SOLL IN DAS FELD und ein anderer AUS DEM LANDT in 321. damit ist es ein KUCHEN Vff die 255. BESTALLUNG ingleichen die 289. GELDER machet man GROSSES HERANTZ und viehl REDENS UON. Es ist aber das erste NOCG NICHT CLAR und kan was E. Ex. die sache mit SELBER CRON dero hohen verstandt nach 747. und den 617. RECHT IM DIRECTORIO FASSEN schon alles dergestalt gemacht werden, das man DOCH DIE CRON 708. SUCHEN und von derselben DEPENDIREN UND BITTEN muss von deren MAN SICH SONSTEN AUSZUHALFETERN GEMEINET. Wegen des andern ist kein vberflues, und erfolget sparsam genug, das sich also die sachen wohl geben, Euer Ex. habe meiner schuldigkeit nach ich dieses mit wenigen gehorsamlichen anfuegen wollen, die ich des allerh¨ochsten schvzs? und dero zu beharrlich gnaden mich vnderthenig empfehle und dero resolution mit sachßen erwarte, Vol. CASSEL den 15. May 1637. Eurer Excelz. Werthiger gehorsamer diener 384.

ich habe mich des EWOLFREN seines Comptorii? et?

Man hat hier in der aller größen geheimb etlich 385. CENTNER METALLISCHE SPEISSE ZUSAMMEN GESCHMELZET und solche verdecket auf 147 gef¨uret, daselbst etliche schon hierzu gemachte STUCKE ZU TAUSCHEN und werden mit dem UFFBRUCH wie ich in vertrauen vernommen den nechsten sich eihlen undt ALLE ABWERTS GEHEN. Alhier wie ich Vermercke wirdt IOHAN VON UFFELN COMMENDANT 571. GUNTEROT aber GEHET MIT ANDEREN ZU FELDT varleßet sich mercken, ob seye etwas UON 703. ALHIER wie auch ANDERE und haben GROSSE HOFFNUNG. Dieses wird gleich bey schließung meines schreibens ahn? EWOLFFEN bey einem gueten ort geschrieben.

And here, I used ChatGPT to translate the letter in the following. Keep in mind that the translated text is an AI-generated translation, where I asked ChatGPT to keep the uppercase written words to show the originally encrypted parts. Clearly, the translation can contain (more) errors introduced by the AI:

1637, May 15

Noble Lord Chancellor and Director, gracious Sir,

Your Excellency, on December 20 of the year 1636 and on February 3 of this year 1637, I humbly informed you of how I, due to unresolved matters, fell into conflict with His Excellency Field Marshal Johan Banner and respectfully requested protection and remedy. Consequently, I turned to the army of Field Marshal Leßel at his request. However, when the conjunction in Meißen recently occurred again, I was warned by good friends not only to be cautious of Field Marshal Banner but also of others, particularly Lord Franz Heinrich of Saxony, concerning the Hamburg matter, as they intended to send men after me. I have therefore retreated to 164., where I still remain. Although I expected to find THE OLD DEVOTION TO THE CROWN in this place, I have discovered that MASTER AND SERVANT HAVE CHANGED GREATLY and at the entire court, except for the 503., THERE IS NOT ONE WHO REMAINS LOYAL TO SWEDEN; INDEED, THE 628. IS FAVORED AND FLATTERED, meaning those who, in HIS ABSENCE,

stood AGAINST the 503. and want to hand over the 764. Therefore, I am quite astonished how L. EWOLFF can negotiate there, as he truly lacks the most essential resources, so much so that I am greatly alarmed. There is talk of a military campaign, WHERE TO IS UNCLEAR. However, it cannot be anything significant, as the forces are not present there, and at present, one is not SUFFICIENTLY 808. 385. 184. TO DRIVE OUT OF THE LAND. The 503. SHALL GO INTO THE FIELD and another OUT OF THE LAND to 321., which makes it a game. On the 255. APPOINTMENT as well as the 289. FUNDS, great attention is being paid and much talk is made. However, the first matter is NOT YET CLEAR and what Your Excellency can make of the situation with THE SAME CROWN according to your high understanding of the 747. and the 617. LAW IN THE DIRECTORY, everything could already be arranged in such a way that one MUST STILL SEEK THE CROWN 708. and DEPEND AND REQUEST from it, from which one otherwise intended to distance oneself. As for the other matter, there is no excess, and it follows sparingly enough that things may well turn out as expected. Your Excellency, I have dutifully wanted to add a few obedient words, in which I humbly recommend myself to the highest protection and your continuous grace, and await your decision with Saxony. Vol. CASSEL, May 15, 1637. Your Excellency’s most worthy obedient servant, 384.

I have used the EWOLFFREN’s office? et?

Here, in the greatest secrecy, about 385. CENTNER OF METALLIC FODDER HAS BEEN MELTED TOGETHER and covertly transported to 147., where several pieces already made for this purpose are to be exchanged, and with the DEPARTURE, as I have learned in confidence, they will hasten in the next few days, and ALL WILL GO DOWNWARD. Here, as I note, IOHAN VON UFFELN will become COMMANDANT 571., but GUNTEROT WILL GO TO THE FIELD with others. It remains to be seen whether anything of 703. will occur here, as well as with OTHERS, and they have GREAT HOPE. This will be written to EWOLFFEN at a good place immediately upon the closing of my letter.

On the last page of the letter, the name of the German city Kassel is also encrypted. This indicates, that the letter was probably sent from or at least written in Kassel.

What the Letter Revealed in a Nutshell

Despite the challenging cryptanalysis and open problems with the nomenclature elements, we were able to decipher significant portions of the letter. The revealed plaintext provided insights into the political and military concerns of the era. Sigismund Heusner von Wandersleben, who served as a Swedish counselor and war commissioner, wrote to Axel Oxenstierna about ongoing conflicts with other military leaders, including Johan Banér and Franz Heinrich of Saxony.

The letter detailed strategic retreats and expressed concerns about potential threats from various factions involved in the Thirty Years’ War. Heusner von Wandersleben sought guidance from Oxenstierna, reflecting the high stakes and pressures faced by those managing the war effort. The letter also addressed financial matters and the deployment of military forces.

Interestingly, the used encryption did not hide all secrets, which were shown within the text. Many information, that seem really important to us, were not encrypted by Heusner while some parts, which contained non-confidential information, were encrypted.

Challenges and Insights Gained

The process of cryptanalyzing and deciphering this letter was both challenging and rewarding. The high number of homophones and the uneven distribution of symbols added a very significant level of difficulty to our cryptanalysis. The absence of an original cipher key meant that we had to rely entirely on CrypTool 2 and the Homophonic Substitution Analyzer to uncover the plaintext. Also, since Michelle is a great expert of old German dialects, her work on the language of the letter and help with the deciphering was crucial. Without her, I would not have been able to decipher and understand the letter to the degree which we were able as a team. So as good as your cryptanalytical tools and efforts may be, there is nothing that can replace a language expert helping you :-).

Our Conclusion

Our combined work on deciphering this 1637 letter has provided interesting insights into the cryptographic practices during the Thirty Years’ War, especially in the German-Swedish relation between Oxenstierna and Wandersleben. The partial decipherment of the letter showed parts of their political and military strategies, while the unresolved nomenclature elements still keep many of their secrets, which we were not able to reveal. Also, this project again shows the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in historical cryptography, combining the linguistic expertise with modern cryptanalytic methods and algorithms.

As I continue my research, I look forward to further exploring the complexities of historical ciphers like this one. Finally, the journey to fully decipher this letter is far from over, since the nomenclature elements are still not deciphered. We hope to find the original key, thus, we are also able to reveal their meanings.

References

[1] Waldispühl, Michelle & Kopal, Nils. (2024). Decipherment of a German encrypted letter sent from Sigismund Heusner von Wandersleben to Axel Oxenstierna in 1637. 10.58009/aere-perennius0116.

[2] DECODE Record 4332: The letter and our analysis results in the DECODE database. URL: https://de-crypt.org/decrypt-web/RecordsView/4332